Imagine a world where the agonizing wait for a life-saving organ transplant is a relic of the past. A future where organ failure is met not with a desperate search for a donor, but with a precision-engineered, biocompatible replacement, crafted from a patient’s own cells. This is no longer the realm of science fiction; it is the tangible, breathtaking frontier of modern biotechnology. The field of bioprinting human organs represents one of the most profound interdisciplinary endeavors of our time, merging advancements in 3D printing, stem cell biology, materials science, and genomics. This article delves deep into the intricate processes, groundbreaking successes, formidable challenges, and far-reaching ethical implications of this technology, which promises to irrevocably transform medicine, redefine life expectancy, and challenge our very conception of the human body.

Section A: Deconstructing the Process – How Bioprinting Human Organs Works

Biomanufacturing organs is a multi-stage, highly sophisticated symphony of biology and engineering. It is far more complex than simply loading cells into a conventional 3D printer.

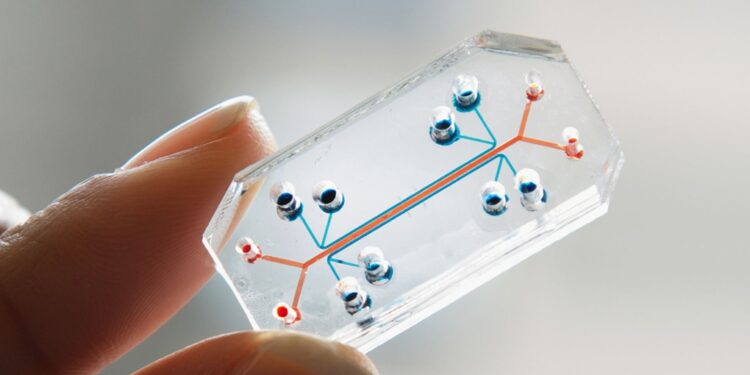

A. The Digital Blueprint: Imaging and CAD Design

The journey begins with advanced medical imaging. High-resolution CT (Computed Tomography) or MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging) scans of a patient’s existing organ or its intended anatomical site are captured. This data is converted into a detailed, three-dimensional digital model using Computer-Aided Design (CAD) software. This model serves as the architectural blueprint, dictating the organ’s exact shape, size, internal vasculature (blood vessel networks), and micro-architecture. Engineers can even modify this blueprint to optimize function or address specific patient defects.

B. The Bioink: The Living “Ink” of Life

This is the core biological material. Bioink is not a single substance but a sophisticated formulation, typically consisting of:

-

Living Cells: Often derived from the patient’s own adult stem cells (like mesenchymal stem cells) or induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs), which are reprogrammed from skin or blood cells. Using autologous cells eliminates the risk of immune rejection.

-

Biomaterials (The Scaffold): A hydrogel or polymer matrix that mimics the extracellular matrix (ECM) the natural scaffolding of tissues. Common materials include alginate (from seaweed), collagen, fibrin, hyaluronic acid, and synthetic polymers like PEG (polyethylene glycol). These materials provide structural support, nutrients, and signals to the cells as they develop.

-

Growth Factors and Signaling Molecules: These biochemical cues are incorporated to guide cell differentiation (e.g., turning a stem cell into a heart muscle cell) and promote tissue maturation.

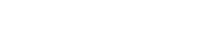

C. The Bioprinter: Precision Deposition of Life

Specialized 3D bioprinters use the digital blueprint to deposit layers of bioink with micron-level precision. The main technologies include:

-

Inkjet-Based Bioprinting: Similar to desktop inkjet printers, it uses thermal or acoustic forces to eject tiny droplets of bioink. It’s fast and cost-effective for certain cell types.

-

Extrusion-Based Bioprinting: The most common method. A pneumatic or mechanical plunger forces bioink through a nozzle, creating continuous filaments. It allows for high cell density and strong structural integrity, ideal for creating larger, more complex tissues.

-

Laser-Assisted Bioprinting: Uses a laser pulse to vaporize a small area of a ribbon coated with bioink, propelling a droplet onto a substrate. It offers exceptional precision and is gentler on sensitive cells but is more expensive.

D. Maturation: From Printed Structure to Functional Organ

The printing process results in a “bioprinted construct.” However, this is merely the beginning. The construct must undergo a crucial phase called maturation in a bioreactor. This sophisticated incubator provides dynamic conditions nutrient flow, mechanical stimulation (e.g., pulsing for a heart tissue, stretching for a lung), and electrical cues that mimic the natural physiological environment. This period, which can take weeks or months, allows the cells to self-organize, form proper cell-to-cell connections, and secrete their own natural ECM, gradually maturing into functional tissue.

Section B: Triumphs and Tangible Applications – From Tissues to Solid Organs

While a fully functional, complex solid organ like a liver or kidney for human transplantation is still on the horizon, the progress has been staggering.

B. Simple Tissues and Hollow Structures (Clinical and Near-Clinical)

-

Skin Grafts: Among the first successes. Bioprinted skin, using layers of keratinocytes and fibroblasts, is being developed for treating severe burns and chronic wounds, offering a superior alternative to traditional grafts.

-

Cartilage and Bone: Custom-shaped cartilage for nasal or ear reconstruction and bone scaffolds for craniofacial repairs are in advanced stages of research and early clinical application.

-

Corneas: Researchers have successfully printed corneal lamellae that could address the global shortage of donor corneas for transplant.

-

Blood Vessels: Creating patent, living vasculature is the holy grail for nourishing larger tissues. Significant strides have been made in printing tubular structures that can facilitate blood flow.

C. Complex, Vascularized Organ Structures (Advanced Research)

-

Mini-Livers and Kidney Organoids: While not full-sized organs, researchers have bioprinted “organoids” or miniature tissue patches that replicate key metabolic functions of livers (detoxification, protein synthesis) and kidneys (filtration). These are invaluable for drug testing and disease modeling and represent critical stepping stones.

-

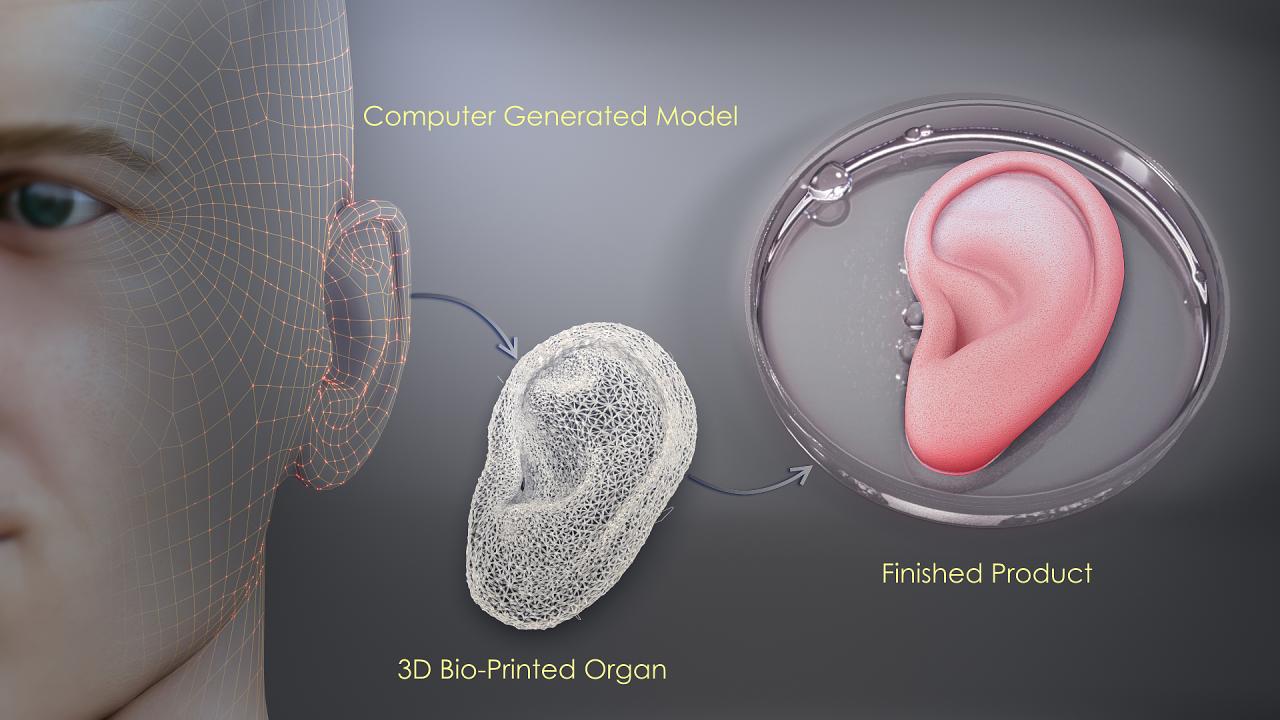

Heart Patches: Cardiac tissue patches, populated with cardiomyocytes (heart muscle cells), have been printed. When implanted, these patches aim to repair areas of the heart damaged by a heart attack, restoring contractile function.

-

Pancreatic Tissue for Diabetes: Efforts are underway to bioprint pancreatic islet cells that can sense glucose and produce insulin, offering a potential functional cure for Type 1 diabetes.

-

Bladders: Relatively simpler hollow organs, lab-grown bladders have already been successfully implanted in patients using earlier tissue engineering techniques, paving the way for bioprinted versions.

Section C: The Colossal Challenges – Barriers to Clinical Translation

The path from lab bench to bedside is fraught with scientific and technical hurdles.

C. Vascularization: The Nutrient Highway

This is the single greatest challenge. Cells cannot survive more than 100-200 microns from a blood supply. Printing the intricate, multi-scale, hierarchical network of capillaries, arterioles, and veins needed to perfuse a thick, solid organ like a heart or liver remains immensely complex. Without immediate, functional vascular integration upon implantation, the core of a bioprinted organ would necrotize and die.

D. Cell Sourcing, Viability, and Maturation

-

Sourcing: Generating the billions of diverse, specialized cells required for a single organ (hepatocytes, endothelial cells, fibroblasts, etc.) from a patient’s stem cells is time-consuming and costly.

-

Viability: The printing process itself can stress or damage cells. Maintaining near 100% viability and function post-printing is critical.

-

Maturation: Accelerating the maturation process in the bioreactor from months to weeks is essential for practical clinical use. Ensuring the tissue develops the correct mechanical strength and electrochemical signaling networks is non-trivial.

E. Immunological Hurdles and Integration

Even with a patient’s own cells, ensuring the final tissue architecture does not trigger an immune response is vital. Furthermore, upon implantation, the bioprinted organ must seamlessly integrate with the host’s nervous system, lymphatic system, and connect perfectly to existing blood vessels and ducts.

F. Regulatory and Manufacturing Challenges

Regulatory bodies like the FDA face the unprecedented task of evaluating the safety and efficacy of living, evolving products. Standardizing the manufacturing process (Good Manufacturing Practice or GMP) for bespoke, patient-specific organs presents a monumental logistical and quality-control challenge.

Section D: Ethical, Social, and Economic Implications – The Double-Edged Sword

This technology carries profound implications that extend far beyond the laboratory.

D. Ethical Quandaries

-

Access and Equity: Will bioprinted organs become a luxury only for the wealthy, exacerbating global health disparities? How do we ensure equitable access?

-

“Designer” Tissues and Enhancement: Could this technology be misused for non-therapeutic human enhancement printing stronger muscles or altered tissues for cosmetic or performance reasons?

-

The Source of Cells: The use of embryonic stem cells, though largely supplanted by iPSCs, remains an ethical flashpoint for some. The sourcing and consent for cell donations require clear frameworks.

-

Defining Life and Identity: At what point does a bioprinted organ, especially something like neural tissue, constitute a “life” or alter a person’s sense of self?

E. Economic and Healthcare Impact

-

Disruption of Transplant Medicine: It could render donor registries, immunosuppressive drugs, and the tragic calculus of organ allocation obsolete.

-

Cost vs. Benefit Analysis: The initial costs will be astronomical, but they must be weighed against a lifetime of dialysis (for kidneys) or chronic disease management. The potential to restore patients to full productivity could have massive economic benefits.

-

Pharmaceutical Testing: Bioprinted human organs offer a revolutionary platform for drug testing and toxicology studies, potentially reducing animal testing and leading to safer, more effective medicines.

Section E: The Future Horizon – What Lies Ahead in the Next Decade

The trajectory points toward incremental but revolutionary progress.

E. Short-to-Mid Term (5-10 years): Widespread clinical use of simpler tissues (skin, cartilage, corneal layers, bone grafts). Increased use of vascularized tissue patches for organ repair (heart, liver). Bioprinted organoids becoming the gold standard for personalized drug screening and complex disease modeling (e.g., cancer).

F. Long Term (10-20+ years): The first successful transplantation of a fully functional, bioprinted solid organ (likely starting with less vascularized organs or using hybrid approaches). Development of fully automated, “print-on-demand” bioreactor systems in major hospitals. Potential convergence with artificial intelligence, where AI designs optimal organ architectures and controls the printing process in real-time.

Conclusion: Redefining the Possible in Human Health

Biotechnology’s quest to print human organs stands as a testament to human ingenuity. It is a challenging, multifaceted endeavor that intertwines cutting-edge science with deep philosophical questions. While significant obstacles remain, the pace of innovation is accelerating. This technology holds the promise of not just extending life, but radically improving its quality, turning terminal diagnoses into manageable conditions. As we stand on the precipice of this new era in regenerative medicine, it is imperative that we advance with both scientific rigor and thoughtful stewardship, ensuring that the future we build is not only technologically awe-inspiring but also equitable and ethically sound. The blueprint for a healthier humanity is being drafted, layer by living layer, today.